Reposted from http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/good-fight_771511.html

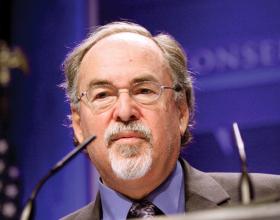

David Horowitz is a political thinker and cultural critic who enjoys challenging leftist shibboleths. His main contribution to contemporary political discourse is a passionate commitment to an outspoken, unabashed, myth-breaking version of conservatism. If communism was the triumph of mendaciousness, he argues in this poignant collection of writings, conservatism cannot accept the proliferation of self-serving legends and half-truths.

This makes his public interventions refreshingly unpredictable, iconoclastic, and engaging. He is a former insider, and his views have the veracity of the firsthand witness. Horowitz knows better than anybody else the hypocrisies of the left, the unacknowledged skeletons in its closet, and its fear to come to terms with past ignominies. He is an apostate who sees no reason to mince his words to please the religion of political and historical correctness. His masters are other critics of totalitarian delusions, from George Orwell to Leszek Kolakowski; in fact, Horowitz’s awakening from his leftist dreams was decisively catalyzed by the illuminating effect of Kolakowski’s devastating critique of socialist ideas. Unlike his former comrades, however, Horowitz believes in the healing value of second thoughts.

Vilified by enemies as a right-wing crusader, Horowitz is, in fact, a lucid thinker for whom ideas matter and words have consequences. His break with the left in the late 1970s was a response to what he perceived to be its rampant sense of self-righteousness, combined with its readiness to endorse obsolete and pernicious utopian ideals. Born to a Communist family in Queens, Horowitz flirted with the Leninist creed as a teenager but found out early that the Communist sect was insufferably obtuse and irretrievably sclerotic. He attended Columbia, where he discovered Western Marxism and other non-Bolshevik revolutionary doctrines. From the very beginning, he had an appetite for heresy.

He joined the emerging New Left and went to England, where he became a disciple and close associate of the socialist historian Isaac Deutscher, author of once-celebrated biographies of Stalin and Trotsky. Thanks to Deutscher, Horowitz met other British leftists, including the sociologist Ralph Miliband (father of the current leader of the Labour party). Consumed by revolutionary pathos, he wrote books, pamphlets, and manifestoes, denounced Western imperialism, and condemned the Vietnam war.

Once back in the United States, he became the editor, with Peter Collier, of Ramparts, the New Left’s most influential publication. In later books, Horowitz engages in soul-searching analyses of his attraction to the extreme radicalism of the Black Panthers and other far-left groups. Under tragic circumstances—a friend of his was murdered by the Panthers—he discovered that these celebrated antiestablishment fighters were fundamentally sociopaths. What followed was an itinerary of self-scrutiny, self-understanding, and moral epiphany. He reinvented himself as an anti-Marxist, antitotalitarian, anti-utopian thinker.

Obviously, David Horowitz is not the first to have deplored the spellbinding effects of what Raymond Aron called the opium of the intellectuals. Before him, social and cultural critics (Irving Kristol, Norman Podhoretz, Nathan Glazer, to name only the most famous ones) took the same path; Bertolt Brecht’s Marxist mentor, Karl Korsch, broke with his revolutionary past in the 1950s. Even Max Horkheimer, one of the Frankfurt School’s luminaries, ended as a conservative thinker. As Ignazio Silone, himself a former Leninist, put it: The ultimate struggle would be between Communists and ex-Communists.

In Horowitz’s case, however, it is a struggle waged by an ex-leftist ideologue against political mythologies that have made whole generations run amok. Like Kolakowski and Václav Havel, Horowitz identifies ideological blindness as the source of radical zealotry. He knows that ideologies are coercive structures with immense enthralling effects—indeed, what Kenneth Minogue called “alien powers.” Putting together his fervid writings is, for him, a duty of conscience. He does not claim to be nonpartisan and proudly recognizes his attachment to a conservative vision of politics. But he is a pluralist: He refuses the idea of infallible ideological revelation, admits that human beings can err, and invites his readers to exercise their critical faculties. He does not pontificate.